Britain and booze throughout history

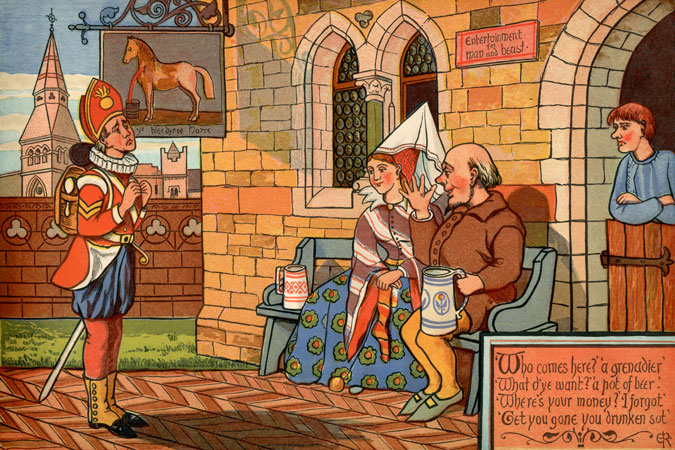

‘Who Comes Here?’, ‘A Grenadier’ – Victorian nursery rhyme illustration (Getty Images). From “Nursery Rhymes – Ridicula Rediviva” illustrated by J.E. Rogers, with chromolith printing by R. Clay Sons & Taylor and published in London in 1876 by Macmillan and Co.

World Cancer Research Fund has been highlighting the links between alcohol and cancer for more than 30 years – but we weren’t the first to do this.

In fact, as Britain recovered after the First World War, beer producers launched campaigns to get people – especially men and boys – back into the pub, with slogans such as “Guinness is good for you” and “Beer is best”. Yet this move by beer makers was a reaction to the thriving temperance movement, which fought back with postcards that said: “Beer is best – for cancer”, listing the cancers alcohol was associated with including brain and mouth.

This is just one aspect of the long history of drinking – and sobriety – in Britain. Did people really drink beer because water was unsafe? Why did people turn to gin? And was Irn-Bru an original tipple of choice for teetotallers? Read on to find out.

Small beer gets bigger

We know through archaeological deposits that people have been drinking beer for around 13,000 years. Beer has certainly been an important drink – especially for poorer people – in the UK for more than 1,000 years. In the Medieval era (around 5th–15th centuries), beer was not just a staple drink. It was also a vital source of calories. At that time, beer and ale were graded according to how long the liquid had been fermented, its strength and the quality of the ingredients. “Small beer” was the weakest and most widely drunk option. Prof Phil Withington of the University of Sheffield says: “Small beer was an integral feature of British diets and was drunk at all times of the day from breakfast.”

A man dressed up as a medieval monk pours himself some beer. Getty Images

However, it’s not true that everyone had to drink beer because the water was unsafe. Most people at this time would have lived in rural areas, and local rivers and streams would have been a source of drinking water. Both beer and ale were safer than some water sources, though, because they are heated during production.

A major change in Britain’s drinking habits occurred in the 1700s onwards with the arrival of gin – dead cheap and often home brewed – which coincided with the start of the industrial revolution, when people moved on mass from rural, family dwellings to less sanitary urban and suburban areas. The pub became a respite for people after working long hours in factories and provided an escape from cramped multi-generational living conditions. “Drink was everywhere; it was economically important and culturally unavoidable,” Dr David Beckingham told History Extra.

Antique advertisement from British magazine: Dinner wine

Gin sends Britain wild

Gin was widely available, low-taxed and – incredibly – sold in pints as people were accustomed to drinking beer in pints. Gin is distilled rather than fermented – which means it’s a lot stronger. Stories we’re familiar with today – around binge drinking, the social impact of alcohol harm (especially when women and poorer people drink to excess), and attempts to curb drinking through public pressure, moral panics and legislation – all began with the Gin Craze. Then as now, alcohol had a class element, with the wine and champagne drunk by the rich seen as less damaging to society and health than the beer and gin of the poor.

And today’s sober curious movement has its history in the anti-drink movements that started at this time. Initially, the backlash against gin focused on temperance – encouraging people to limit their alcohol consumption, mainly by drinking weaker but still alcoholic drinks. The 1830 Beerhouse Act allowed people to brew beer from home – an attempt to reduce gin drinking. However, some strands of the movement favoured total abstinence.

The Band of Hope, established in 1847, became the biggest temperance organisation in Britain, with 3.5 million members by the end of the 19th century. It was a youth-led movement, and part of the attraction was that it offered young people an (often cheaper) alternative to the pub. As well as pressurising members with signed pledges, badges and magazines, temperance societies organised fun stuff: brass bands, sober cafes, music hall events and outings. The first temperance day trip was an excursion from Leicester to Loughborough in 1841, for 500 temperance society members. The man who arranged it was none other than Thomas Cook – the inventor of package holidays.

So what alcohol-free drinks were around in the 18th and 19th centuries? Initially, most concoctions were mixes of readily available herbs and water, often heavily sweetened: sarsaparilla “wine”, dandelion and burdock, cream soda and ginger beer – as well as tea. Some of the biggest brands in soft drinks also emerged at this time. Teetotallers drank fortifying iron brew (later Irn Bru), Coca-Cola and Vim Tonic, as well as milk drinks – precursors of today’s milkshake and bubble tea bars.

It wasn’t plain sailing for those trying to cut back on alcohol though. The temptations of alcohol versus the guilt of overindulgence are revealed in the diaries (written between 1830 and 1881) of Nottingham solicitor and mayor William Parsons, who talks about his attempts to go dry in January, and how hard it was to avoid booze in social gatherings: “Tea totalism in my position is not carried out without great difficulty.”

As well as persuading individuals to change their drinking habits, people who advocated for drink-free living leaned on politicians to legislate for restrictions on the sale of alcohol, and taxation to reduce its availability and affordability. The fact that we’re trying the same approaches hundreds of years later shows the difficulty of breaking up Britain’s relationship with the booze.

Temperance as a movement died off from the 1950s as alcohol became even more widely marketed and socially acceptable. This is perhaps reflected in the licensing changes. Since 1988, pubs have been able to open all day and 24-hour licensing was introduced in 2005. Despite this, younger generations seem to be drinking less than their elders. In England’s 2022 health survey, the highest prevalence of drinking on at least 1 day a week was among adults aged 65–74, whereas the lowest was among 16–24-year-olds (60% vs 36%).

Our theme for Cancer Prevention Action Week is Alcohol and cancer: let’s talk. The UK’s long history of drinking – and staying sober – shows that alcohol is deeply embedded in British society. Yet even though we’re no longer in the midst of a gin craze, the harms of alcohol are widespread. As those abstinence campaigners at the start of the last century knew, alcohol is a cancer-causing, psychoactive, toxic, and dependence-producing substance linked to more than 200 health conditions. Everyone deserves to know the history – and the truth – about alcohol.