Tackling alcohol harm needs to be top of Keir Starmer’s to-do list

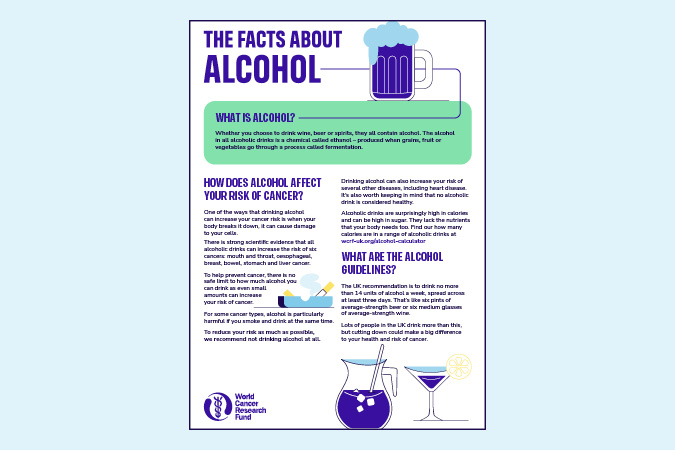

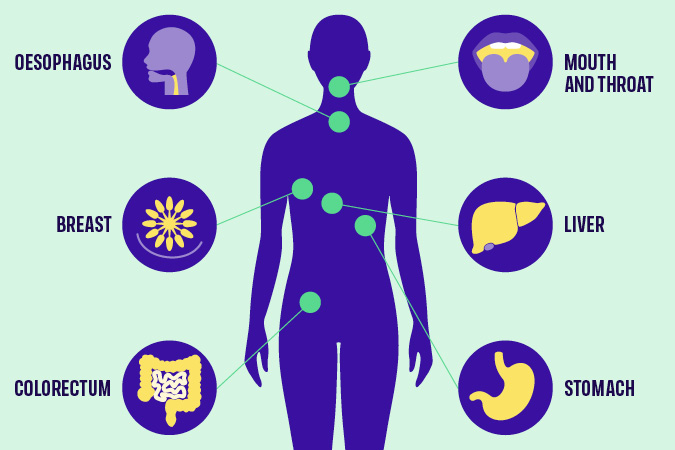

Alcohol is a proven risk factor for 7 cancer types, and our evidence clearly shows there is no safe level of consumption when it comes to preventing cancer. Each year 17,000 people – 46 people every day – are diagnosed with a cancer caused by alcohol.

Alcohol deaths in England reached nearly 10,500 in 2023, a massive 42% increase since 2019. Despite these tragic statistics, alcohol policy across the UK remains woefully inadequate, doing very little to mitigate its significant harms, including cancer, and the immense burden it places on the NHS.

Making the case for change

Which cancers are linked to alcohol?

That’s why this year, our flagship campaign – Cancer Prevention Action Week – focuses on the links between alcohol and cancer, aiming to ensure that everyone can make informed decisions about their alcohol consumption. While raising awareness is important, it must be combined with evidenced-based polices that enable and support people to make healthier choices.

As many aspects of alcohol policy are the responsibility of the devolved administrations, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales all have alcohol strategies in place. In contrast, England has not had a National Alcohol Strategy since 2012.

We’re calling on the UK government to introduce a long overdue National Alcohol Strategy for England without delay. The Strategy must introduce policies on labelling, pricing and marketing – 3 interventions that have strong evidence of positive impact. Crucially, it must also remain independent of industry influence.

1) Labelling

Despite being carcinogenic, alcohol is exempt from mandatory health warning labels. Unlike other food and drinks, alcohol labels are also not required to include information on nutritional content or calories. As the Alcohol Health Alliance puts it, there is more product information on a bottle of orange juice than on a bottle of beer. In fact, alcoholic drinks only have to display to display minimal information such as the name, strength as alcohol by volume (but only if over 1.2%), allergen information and the best before date (if the drink’s strength is under 10%). Even pregnancy and drink driving warnings are voluntary.

Consumers have a right to know about every product’s health risks and harms. Introducing health warning labels on alcohol that highlight cancer risk, alongside information on nutrition and calories, is an easy and effective way to ensure this. Evidence shows that effective labelling can prompt behaviour change and lead to reduced consumption.

For labelling to be effective, it must be clear, plain, distinct and mandatory. Additionally, labels should not include ambiguous language such as “drink responsibly”. Our policy position on alcohol explains that the use of QR codes to link to health information must be prohibited as, rather than informing people about risks, they provide marketing opportunities by redirecting consumers to producers’ websites.

2) Pricing

Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) has been introduced in Scotland and Wales, but not in England or Northern Ireland. It sets a baseline price at which a unit of alcohol can be sold and targets cheap, strong alcohol that is often consumed by adolescents and other vulnerable groups.

Public Health Scotland’s review indicates that MUP has reduced alcohol-specific deaths by 13% and averted over 800 hospitals admissions every year since its introduction in 2012. MUP was found to have the most impact on those living in the 40% most deprived areas of Scotland, helping to reduce health inequalities. The Welsh government has also seen the benefits of MUP, which it introduced in 2020. Northern Ireland has consulted on proposals to introduce MUP.

England must follow suit, introducing MUP at 65p and adjusted for inflation thereafter. Without MUP in England, a 2.5 litre bottle of cider containing 19 units of alcohol can be bought for as little at £5.25. Under a 65p minimum unit price, this would rise to £12.19. Industry opposes MUP, arguing that it would damage sales in pubs and restaurants. However, most alcohol sold in these settings is already above minimum unit prices.

3) Marketing restrictions

Marketing restrictions on alcohol remain woefully inadequate. Advertising regulations prohibit linking alcohol with youth, irresponsible behaviour or social success, but enforcement is ineffective. The Advertising Standards Agency has no power to issue fines or sanctions, and often rules on complaints only after a campaign has ended. Like labelling, advertising is not a devolved issue, meaning the picture across the UK is largely the same.

Alcohol advertising is widespread, despite strong evidence linking exposure to alcohol marketing with young people drinking more and at an earlier age. The UK’s insufficient restrictions must be addressed by classifying alcohol as an “unhealthy product” under high fat, sugar or salt (HFSS) marketing restrictions. This would limit its promotion, particularly to vulnerable populations including children and adolescents.

The time to act is now

No family should have to endure the devastating trauma of alcohol-related cancer. Yet, as a result of the rise in high-risk drinking since the coronavirus pandemic, the UK could see more than 18,000 additional cancer cases by 2035.

Join us this Cancer Prevention Action Week to demand action. Sign and share our petition today, calling for a National Alcohol Strategy for England.

- The Alcohol Health Alliance, which we are a member of, has more information on MUP, labelling and marketing restrictions.